New medical device labeling system goes global

January 23, 2013

by Brendon Nafziger, DOTmed News Associate Editor

New medical device labeling designed to make tracking products through the supply chain easier is coming to the United States in the next year or so, but it's also poised for adoption in Europe and elsewhere. And the global spread of the system could help clinicians better understand what happens to devices after they hit the market.

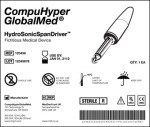

The Unique Device Identifier system, which was again mandated by Congress in a Food and Drug Administration user fee bill over the summer, is a two-part system that involves a machine-readable label, such as a bar code, and human-readable text. Backers of the UDI system believe a universal labeling system could be a boon for health care, allowing materials managers to get a better handle on their inventory and to comply quicker for recalls of defective products.

But some experts also think the system — especially as it goes global or gets hooked into electronic health records — could help patch over gaps in medical device epidemiology, enabling researchers to study how devices fail and even how they stack up against each other out in the real world.

What happens is, after medical devices get released, government regulators sometimes insist that manufacturers run post-market surveillance studies to provide more evidence on the safety or effectiveness of the device. But post-market data is often "thin on the ground," in the words of one researcher.

"Its difficult to find good data on devices after they're approved," Dr. Joseph Drozda, a physician with the four-state regional Mercy health system who's running a study on building a UDI-related database for device epidemiology, told DOTmed News.

And thanks to wider adoption of the UDI and projects like Drozda's, that could change.

Going abroad

In the United States, UDI rules have been in the works for years, but legislation over the summer likely helped kick-start the process again. In a user fee bill, Congress ordered the FDA to release proposed rules for the system by the end of the year. The agency released those draft rules in July, and final regulations are expected as early as this spring, with the system applying to higher-risk products within one year of their publication.

The next stop after the U.S. is probably Europe. Likely prompted in part by a scandal around a French breast implant maker that sold dodgy implants with a high rupture rate, on Sept. 26, the European Commission issued a proposed directive on reforming the medical device process. The directive, which still has to be approved by the European Parliament, included adopting the UDI, and building and expanding a continent-wide, publicly available device database, called Eudamed.

In their announcement, the European Commission said the UDI would have a three-pronged goal: enhancing post-market surveillance, reducing medical errors and fighting counterfeit products. The EC also said it envisioned a "risk-based" approach to UDI, possibly indicating Europe is taking a path similar to the FDA, where riskier devices, like implants, get labeling first.

"It's still a little vague," Karen Conway, director of industry relations at GHX, a supply chain consulting firm, told DOTmed News. "They have not provided a lot of specifics. They do say they expect to have their final directive out by 2014 and it would be a phased implementation by 2019. UDI is just one piece of that."

Still, she said in broad outline, the rules will probably resemble what the FDA has done, as European regulators were participants in the Global Harmonization Task Force, a body that sought to harmonize device rules around the world, and whose suggestions were taken into account when it came time for the FDA to draft its own UDI platform.

The difference, if any, could be in the traceability requirements, Conway said, with the Europeans likely calling for more robust "track and trace" measures to aid recalls.

Not only Europe

It's not just Europe, though. Other countries are mulling over adopting UDI, too. "China is looking very seriously at it," Conway said. Australia and some South American and Southeast Asian countries are also considering adopting the device standards, she said. "This is definitely becoming a global type of regulation."

The more countries that adopt UDI, potentially the greater the benefits. If a device is identified the same way in, say, a registry kept at Kaiser Permanente, an integrated health system in California that maintains its own device logs, and at registries in Germany, then you have much larger databases to keep track of how devices are being used and how they're performing, Conway said.

"So you're starting to not only have data in electronic medical records — 'Joe Smith got this hip replacement' — but you're also starting to have much more data around public health, 'Men over 40 receiving this particular hip have this outcome,' Conway said. "You can start doing more epidemiological work."

Here the FDA appears to agree. In a public workshop this summer, Danica Marinac-Dabic, the director of the Division of Epidemiology within agency, stressed the importance of "global capabilities" around the UDI.

"Although the focus clearly is on the national infrastructure, we would like very much to harness the resources, the data sources from around the globe," she said, according to a transcript of the workshop on the FDA's site. "As you know, medical device technology reaches markets sometimes sooner in other countries, and both in pre-market and post-market, we are very committed to be able to use that information...as we help industry to design their studies to meet approval for the FDA. "

Towards epidemiology

The FDA is already helping to sponsor research to see if the UDI could help play a role in device epidemiology.

For instance, at Mercy headquarters in a St. Louis suburb, Drozda's team is working on a demonstration project for the Medical Device Epidemiology Network, or MDEpiNet, which would use a database filled with searchable attributes linked to the UDI to help doctors or researchers watch products through the supply chain. For researchers, this means more powerful post-market studies and comparative effectiveness research, Drozda said. They can start to compare one company's device, say a lead wire, against another company's, but by having access to attributes across all devices and manufacturers, you could design queries for the database just focusing on one attribute. For lead wires, for instance, you could see whether leads under a certain diameter were more prone to fracturing, Drozda said. "The attributes let you do a lot more sophisticated analyses."

They also give the FDA a better grasp on relative safety, by giving both adverse events for a device and what's known as "exposure," or the amount of people who are known to have used the device or have had it implanted. "So they can see we've gotten four (adverse event) reports with this out of 1,000 of those things implanted," Drozda said.

The system could also help doctors at the point of care. According to Drozda, ideally, based on their demonstration project, it would work like this: an item comes into the cath lab or operating room, the doctor or nurse scans it, and then based on the UDI, the staff could access an attributes database linking to relevant clinical characteristics that could even help drive care decisions.

"They'd have a lot of information available to them, simply by scanning the bar code that has the UDI on it, " Drozda said.

As part of the implementation of the UDI, the FDA is creating its own database, the Global UDI Database, but Drozda said because of regulatory implications, it could be "cumbersome" to add or remove device attributes to the database that might have clinical significance and would be interesting to a doctor or researcher. The attribute database being developed by Drozda, however, would be more flexible.

Right now, in the demonstration project, Drozda's team is building a database only for stents, which includes at least nine attributes, such as length, material, and whether it's impregnated with a drug. The reason for starting with stents is simple, Drozda says. "It's a finite universe you can get your arms around." There are only three manufacturers (at least in the United States), the science is fairly well established, and manufacturers are often willing to share data. But later, Drozda said they'd hope to expand it to areas with potentially more safety and comparative effectiveness issues, such as implantable cardiac defibrillators, ICD wires and hip and knee replacements.

"We'll get our feet wet with something a little less controversial," he said.

The first phase of the demonstration project at Mercy, which will include the system's cath labs throughout Missouri and Arkansas, goes through the rest of the year, and Drozda said his team is looking to drum up funding for the second phase of the project.

The Unique Device Identifier system, which was again mandated by Congress in a Food and Drug Administration user fee bill over the summer, is a two-part system that involves a machine-readable label, such as a bar code, and human-readable text. Backers of the UDI system believe a universal labeling system could be a boon for health care, allowing materials managers to get a better handle on their inventory and to comply quicker for recalls of defective products.

But some experts also think the system — especially as it goes global or gets hooked into electronic health records — could help patch over gaps in medical device epidemiology, enabling researchers to study how devices fail and even how they stack up against each other out in the real world.

What happens is, after medical devices get released, government regulators sometimes insist that manufacturers run post-market surveillance studies to provide more evidence on the safety or effectiveness of the device. But post-market data is often "thin on the ground," in the words of one researcher.

"Its difficult to find good data on devices after they're approved," Dr. Joseph Drozda, a physician with the four-state regional Mercy health system who's running a study on building a UDI-related database for device epidemiology, told DOTmed News.

And thanks to wider adoption of the UDI and projects like Drozda's, that could change.

Going abroad

In the United States, UDI rules have been in the works for years, but legislation over the summer likely helped kick-start the process again. In a user fee bill, Congress ordered the FDA to release proposed rules for the system by the end of the year. The agency released those draft rules in July, and final regulations are expected as early as this spring, with the system applying to higher-risk products within one year of their publication.

The next stop after the U.S. is probably Europe. Likely prompted in part by a scandal around a French breast implant maker that sold dodgy implants with a high rupture rate, on Sept. 26, the European Commission issued a proposed directive on reforming the medical device process. The directive, which still has to be approved by the European Parliament, included adopting the UDI, and building and expanding a continent-wide, publicly available device database, called Eudamed.

In their announcement, the European Commission said the UDI would have a three-pronged goal: enhancing post-market surveillance, reducing medical errors and fighting counterfeit products. The EC also said it envisioned a "risk-based" approach to UDI, possibly indicating Europe is taking a path similar to the FDA, where riskier devices, like implants, get labeling first.

"It's still a little vague," Karen Conway, director of industry relations at GHX, a supply chain consulting firm, told DOTmed News. "They have not provided a lot of specifics. They do say they expect to have their final directive out by 2014 and it would be a phased implementation by 2019. UDI is just one piece of that."

Still, she said in broad outline, the rules will probably resemble what the FDA has done, as European regulators were participants in the Global Harmonization Task Force, a body that sought to harmonize device rules around the world, and whose suggestions were taken into account when it came time for the FDA to draft its own UDI platform.

The difference, if any, could be in the traceability requirements, Conway said, with the Europeans likely calling for more robust "track and trace" measures to aid recalls.

Not only Europe

It's not just Europe, though. Other countries are mulling over adopting UDI, too. "China is looking very seriously at it," Conway said. Australia and some South American and Southeast Asian countries are also considering adopting the device standards, she said. "This is definitely becoming a global type of regulation."

The more countries that adopt UDI, potentially the greater the benefits. If a device is identified the same way in, say, a registry kept at Kaiser Permanente, an integrated health system in California that maintains its own device logs, and at registries in Germany, then you have much larger databases to keep track of how devices are being used and how they're performing, Conway said.

"So you're starting to not only have data in electronic medical records — 'Joe Smith got this hip replacement' — but you're also starting to have much more data around public health, 'Men over 40 receiving this particular hip have this outcome,' Conway said. "You can start doing more epidemiological work."

Here the FDA appears to agree. In a public workshop this summer, Danica Marinac-Dabic, the director of the Division of Epidemiology within agency, stressed the importance of "global capabilities" around the UDI.

"Although the focus clearly is on the national infrastructure, we would like very much to harness the resources, the data sources from around the globe," she said, according to a transcript of the workshop on the FDA's site. "As you know, medical device technology reaches markets sometimes sooner in other countries, and both in pre-market and post-market, we are very committed to be able to use that information...as we help industry to design their studies to meet approval for the FDA. "

Towards epidemiology

The FDA is already helping to sponsor research to see if the UDI could help play a role in device epidemiology.

For instance, at Mercy headquarters in a St. Louis suburb, Drozda's team is working on a demonstration project for the Medical Device Epidemiology Network, or MDEpiNet, which would use a database filled with searchable attributes linked to the UDI to help doctors or researchers watch products through the supply chain. For researchers, this means more powerful post-market studies and comparative effectiveness research, Drozda said. They can start to compare one company's device, say a lead wire, against another company's, but by having access to attributes across all devices and manufacturers, you could design queries for the database just focusing on one attribute. For lead wires, for instance, you could see whether leads under a certain diameter were more prone to fracturing, Drozda said. "The attributes let you do a lot more sophisticated analyses."

They also give the FDA a better grasp on relative safety, by giving both adverse events for a device and what's known as "exposure," or the amount of people who are known to have used the device or have had it implanted. "So they can see we've gotten four (adverse event) reports with this out of 1,000 of those things implanted," Drozda said.

The system could also help doctors at the point of care. According to Drozda, ideally, based on their demonstration project, it would work like this: an item comes into the cath lab or operating room, the doctor or nurse scans it, and then based on the UDI, the staff could access an attributes database linking to relevant clinical characteristics that could even help drive care decisions.

"They'd have a lot of information available to them, simply by scanning the bar code that has the UDI on it, " Drozda said.

As part of the implementation of the UDI, the FDA is creating its own database, the Global UDI Database, but Drozda said because of regulatory implications, it could be "cumbersome" to add or remove device attributes to the database that might have clinical significance and would be interesting to a doctor or researcher. The attribute database being developed by Drozda, however, would be more flexible.

Right now, in the demonstration project, Drozda's team is building a database only for stents, which includes at least nine attributes, such as length, material, and whether it's impregnated with a drug. The reason for starting with stents is simple, Drozda says. "It's a finite universe you can get your arms around." There are only three manufacturers (at least in the United States), the science is fairly well established, and manufacturers are often willing to share data. But later, Drozda said they'd hope to expand it to areas with potentially more safety and comparative effectiveness issues, such as implantable cardiac defibrillators, ICD wires and hip and knee replacements.

"We'll get our feet wet with something a little less controversial," he said.

The first phase of the demonstration project at Mercy, which will include the system's cath labs throughout Missouri and Arkansas, goes through the rest of the year, and Drozda said his team is looking to drum up funding for the second phase of the project.